The Physics and Art of Beautiful Music

Coldplay’s classic 2000 hit “Yellow” is anchored by a 22-second guitar riff, unremarkable except perhaps in how incredibly simple it is. It contains only 5 distinct notes arranged into 8 two-note chords (a chord being a group of two or more notes played together) played in predictable pattern with no rhythmic variation. I am confident someone who has never played a guitar could learn to play it in about 5 minutes, and would not be surprised if a non-human primate can or has already been taught to play it.

So how is it that such a basic collection of notes has captured millions of listeners? Sure, appreciation of a song is subjective, but “Yellow” has been an unambiguous success both commercially and critically. Part of it can be explained mathematically – there are relationships between these 5 notes that produce harmonies that we have assumed for centuries to be inherently sonically pleasing. However, recent research has suggested – contrary to what many had accepted to be true – that these “pleasant” harmonies are pleasant only because of cultural exposure to similar sounds, a bias driven by centuries of musical development. Scientists have begun to explore what factors beyond these simple harmonies cause our brains to enjoy a song. The more they learn, the more it appears impossible to examine the objective physical and mathematical patterns in music without also exploring the cultural and personal tendencies of music preference in the second. The crossroads at which music is born is a busy and unplanned intersection of physics, art, musical intuition, and listener’s preference which converge and produce beautiful (to some) music.

Some clarifying points to set the stage for our discussion of physics and psychology:

-

There are objective physical and mathematical relationships between notes. These relationships are patterns that can be described mathematically and are independent of cultural upbringing or preference. Groups of notes that we call “consonant intervals” are consonant because of the pattern of displacement of air molecules that make up sound waves. They are consonant to Chicago natives, Pacific Islanders, and Martians alike. Cultural influences appear when we ask if consonant intervals sound “pleasant” or not. This MIT article describes research suggesting that consonance may be unrelated to music’s appeal, despite most Western listeners agreeing that consonant intervals sound pleasant.

-

All that said, I believe it is still worth exploring the connection between a harmony’s (objective) mathematical structure and the (subjective) response it evokes for listeners, even though the latter may be radically different for different groups of people. “Yellow” has sold over half a million copies; while it may not be an “objectively” better piece of music than any other, enough people like it that there must be something appealing in its composition.

-

Some might say this article has a narrow, Western/Anglo-American paradigm. They’d be right – that’s the music I’ve grown up with, and the song we analyze here belongs in this category. This narrowness may be impossible to avoid – after all, music is a subjective experience. It is written for culturally conditioned listeners by culturally conditioned musicians. While this analysis might not be universally applicable, it reveals a bit about the elaborate mechanisms that cause us to enjoy music, and reminds us of how incredibly powerful and complex our minds can be.

Dissecting the 6 chords (of the 8, two are repeated, so there are 6 distinct chords) of Yellow’s intro reveals significant patterns in how each chord’s constituent notes differ from each other. Sounds are waves – rather than alternating high peaks and low troughs like an ocean’s wave, sound waves alternate between pockets of compressed air (the “peaks”), and rarefied, or expanded, air (the “troughs”).

This basic sine wave represents a note – the vertical axis shows changes in the air pockets’ density as the wave travels from left to right through space.

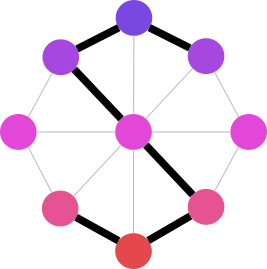

It could be any note, but we will say it has a frequency of 494 Hertz, the sound wave musicians call a B4 (notes of a given letter are an “octave” apart; each octave doubles the frequency. A B3 is 247 Hz, etc, down to B0, 30.9 Hz, the lowest audible “B”). The graph has vertical lines at the start of each new wave. Being at 494 Hz, 494 of these waves pass over our eardrums each second when we hear a B4; in other words, 494 pockets of compressed air and 494 pockets of rarified air hit our ears, and our brain converts that into a sound that has the pitch of a B4 note. The 8 chords of intro to Yellow all have the B4 note; it is only the second note of the chord that changes. The following graphs will show the relationship between that changing second note and the constant B4 note (which here we will just call “B”).

The first two chords: F#/B and E/B – called perfect fifth and perfect fourth intervals respectively (musical intervals of higher degree mean the notes are further apart).

As the MIT article explains, these intervals have “perfect consonance”. The physical meaning of this term is that the frequencies of the notes are multiples of each other – F# (740 Hz) and B (494 Hz) have a ratio of 3:2 between their frequencies. If the two waves start at the same place, after three waves of F# and two waves of B, the waves “line up” at the highlighted points of the graphs – they both have a perfectly aligned starting point (meaning they both have a pocket of air at the same time with zero compression and zero rarefaction). E and B have the same property, with a 4:3 ratio.

This conversation about cold, hard physics must get interrupted here by cultural and personal perception. In Western music, these intervals play a key part of how melodies and harmonies are constructed. “Here Comes the Bride” – a perfect fourth. “Twinkle Twinkle Little Star” – the first two words are sung a perfect fifth apart. Most people who grew up listening to Western music find these melodies pleasant (again, see the MIT article). And there is a very real basis to this consonance, as shown in the graphs of the sound waves. In fact, playing a B4 note can cause a string tuned to E or F# to vibrate seemingly spontaneously – the perfect alignment of the sound waves can cause a string to vibrate without the musician touching the second string. Consonance exists objectively, but the key to remember is that its appeal or lack thereof is subjective. But also important to understand is that musicians and listeners are products of their culture, and composers make use of that fact – hence the composers of “Yellow” beginning with intervals subjectively perceived as “strong” and “pleasant”.

In the song’s next four chords, the guitar takes advantage of dissonance and our cultural preference and expectation for consonance. The chords and intervals progress from A#/B (major seventh) to G#/B (major sixth) to C#/B (major second) to B/B (unison; the same note is played on two different strings simultaneously). The major seventh and second are dissonant intervals, whereas the sixth and unison are consonant. Dissonance is harder to define than consonance, but, mathematically, the wavelengths are related by a much higher and less exact integer ratio. Specifically, the major second’s frequencies are at a 9:8 ratio. The major seventh’s are roughly 15:8, but closer to 15.1:8; the waves’ peaks and troughs do not line up as they do in the other intervals we have examined.

Many listeners of Western music expect music to go from dissonant patterns to consonant patterns. While this may not be an innate human preference, it is an expectation that is accounted for and catered to by composers. When “Yellow” features the dissonant major seventh, listeners expect resolution (a term meaning movement from dissonance to consonance). This expectation is analogous to our expectation of plot resolution at a movie or novel’s climax. At a scene of conflict or a dilemma, we lean forward in our seats in anticipation of the good guys’ victory or solving of the mystery that has been building. At the resolution, we lean back with satisfaction. If the mystery is left unsolved and the movie ends abruptly, viewers would feel a strong sense of disappointment grounded in the cultural conditioning of seeing dozens of movies that resolve the conflict with some finality. Similar tension and suspense is created in the three seconds that we listen to the seventh and second chords. The resolution to consonant chords provides the psychological satisfaction.

Outside of a few music nerds, not many would immediately describe listening to Coldplay playing a A#/B chord as a suspenseful experience begging for a release of tension. But subconsciously, the expectations built over years of listening to music do create this back-and-forth of tension and resolution. While we may not be aware of it, this is a key part of what glues our attention to our favorite songs.

The 22 seconds of music analyzed here involve countless intricate interactions – between strings and air molecules, among sound waves, and among the neurons that hold the memories of the music we grew up on and dictate how we react to new music. Perhaps you regret spending ten minutes on this article, and would rather just go back to appreciating music without a wordy and unnecessarily detailed dissection of your favorite songs. After all, composers and listeners of music create and experience beautiful melodies usually without consciously resorting to a note-by-note examination of sound waves, psychological reactions, and cultural biases. That perhaps leads to the most fascinating lesson about the human brain on music. Books and research papers have been written trying to deconstruct the many elements that make music enjoyable. Yet even without the benefit of these thousands of pages of research, our brains are able to take all these elements of physics, math, emotion, psychology, and culture as inputs – and the output we produce is the experience of beautiful music.

The Syntact Project

The Syntact Project